Book Provenance: Exhuming Jackson's Price-Codes

JACKSON, Ian [as ‘Exhumation’

(pseud.)]

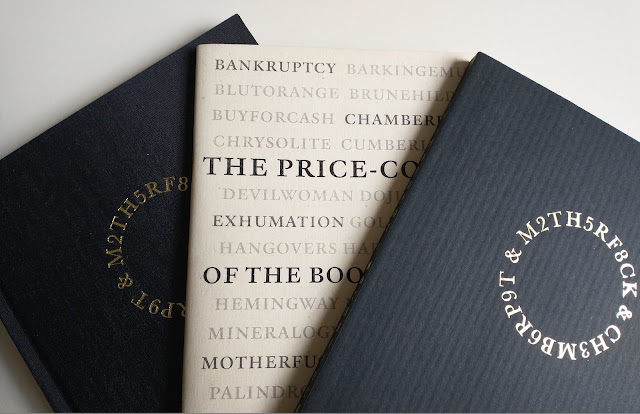

Ian Jackson, 2010. First Ed., booklet, 500 copies

Bruce McKittrick, 2017. Second (Revised) Ed., 310 copies

The majority of examples Jackson gives are book-codes created and used by booksellers, to mark either the intended selling price of the (second-hand) book or the price the book was acquired for. Or sometimes both. When and where the book was acquired—year, month, auction, house clearance, online, etc—might also be recorded. Codes would sometimes pass down through generations of booksellers or multiple bookshop owners. For the most part, Jackson avoids publishing the key to codes still current. Several book-collector's codes are also discussed. It is a fascinating (and amusingly written) piece of work.

After reading it, I felt compelled to contact the author; and also compelled to invent some of my own price-codes (see below). My email was rambling. I tried to say that the book felt (at that moment) like it represented much of my current thinking and approach to reading and book-collecting; which is true. He didn't reply. I then discovered that I had bought my copy of Price-Codes from Peter Kidd, the author of the Afterward. He informed me that Jackson had died a few years ago.

.jpg) |

| Personal (trial) codes |

What struck me most, upon reflection, is how many booksellers' prices I'd likely erased over the years, and how little attention I'd given to other unintelligible—but possibly related—markings. Some of these could have been booksellers' codes, others may have been previous owners' marks. I did this despite having an interest in, and genuine awareness of, book provenance.

In my (un-read) email to Jackson I

summed up this behaviour as: ‘the modern (contradictory) position in

book-collecting of the total avoidance of marking (pejorative) books, while

still recognising provenance as important’; adding my belief that this comes

from ‘an almost pathological obsession with conformity’ and the ‘belief in the

hyper-importance of condition’. I still believe this to be largely true, especially of present-day Tolkien book-collecting; or, at least, this is how it often manifests itself online (to me). A generalisation, to be sure.

Book-collectors are often very interested in book provenance when it comes to signed copies, association copies, and similar; because good provenance can provide “proof” of authenticity, gives confidence to the buyer, and is often interesting in itself. And while there is certainly also a general interest in book provenance when it, for example, reveals some new bibliographical detail, there is little or no appetite for engaging in practises that will create evidence of ownership for future collectors and researchers; for example adding ownership marks, purchase details, marginalia, etc. Future provenance research will be impoverished as a result. I'm not arguing for this to be remedied; it is simply (for now) an observation.

After years of collecting books, and Tolkien in particular, I have become more and more interested in books

that ‘tell a story’; a copy of The Silmarillion that tells a story—one with copy-specific features—even better. I've never avoided collecting books that had previous ownership

markings or marginalia; although, those first edition copies of The Silmarillion with 1977 Christmas gift inscriptions, really aren't very interesting. But (in general) returning to older books from one's collection—books that exhibit interesting provenance—continues to be rewarding; new stories are often revealed, new perspectives gained.

%202.jpg) |

After consuming Jackson's book, I bought and read David Pearson's Provenance Research in Book History: A Handbook (The Bodleian Library / Oak Knoll Press, New and Revised Ed., 2019), which I would highly recommend to anyone interested in reading about the subject in more detail. Jackson's Price-Codes is discussed in chapter two, pp. 58–61 (‘Booksellers' codes’). Peter Kidd's review of the 2019 edition—published in The Book Collector, vol. 68 (2019), pp. 574–576—is also well worth reading, if you can track it down. I might also add that this book is very well made, nicely printed and solidly bound. As is only fitting, I annotated my own copy throughout.

|

Further information on Ian Jackson and his publications can be found here [BROKEN LINK www.ianjacksonbooks.com].

Peter Kidd has a professional interest in provenance research; his highly interesting MEDIEVAL MANUSCRIPTS PROVENANCE blog can be found here.

![[The] Silmarillion; book-collecting minutiae](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/a/AVvXsEi7NXZeS-e6C3roxz2c7UWFEcUEINpMfgDkihMCeoVgjBGA-K9_wE7HmJ0J5LSIJqNm8fDVUqJ5HOvdvgIHgPctu9xPEx_CjPUqrXJEyd5Q-ftA4tlo6NhRx3V9JZl-IBbGvIvBQVjE9GFyKMqd_JrWwkLEqMMbhG2m3Q3FQuyhnjhlhdpebGxovD9adS1H=s456)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment