Philobiblon: Quod Thesaurus Sapientiae Potissime Sit In Libris

I find most books-about-books interesting, but there can't be many works on book-collecting—that remain relatable and not mere historical curiosities—from the medieval period. The Philobiblon was written by Bishop and bibliophile Richard de Bury in the year (or years) prior to his death in 1345. The title, ‘Philobiblon’, was a word coined by de Bury himself, and translates roughly as ‘love of books’. It promotes the virtues of reading and writing, as well as—what the work is best known for—book-collecting. It can almost be read as a sort of manifesto of the latter.

|

| Philobiblon (1960) |

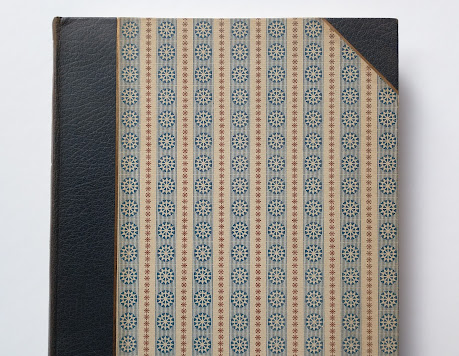

I was attracted to this particular copy of the book for (several) very specific reasons, entirely unrelated to the content. I'd never previously heard of the Philobiblon. Firstly, it was an attractive looking book; designed by Ruari McLean, in half-leather, with a very traditional looking paper board covering. This edition was also published (in 1960) in honour of Sir Basil Blackwell's birthday; he'd turned seventy in May 1959.

|

| Edition notice |

The Blackwell name is inextricably linked with Oxford, books, and Tolkien. Blackwell's had a long association with Tolkien, Basil Blackwell having published Tolkien's poem ‘Goblin Feet’ in 1915. From Scull & Hammond's Reader's Guide we also know that Tolkien and Basil Blackwell were neighbours for a time, at Northmoor Road, in the 1920s; Tolkien bought Blackwell's house and moved into it (with family) in 1930. See Scull & Hammond's The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion & Guide: Reader's Guide (HarperCollins, 2006, p. 118) for further detail.

One could tease out further connections; even a few—at several removes—to The Silmarillion. It's a stretch. By 1975, BLACKWELL PRESS—the printing arm of the Blackwell's group—owned BILLING & SONS; who were, of course, responsible for the printing (in 1977) of part of the first edition of The Silmarillion. BLACKWELL'S BOOKSHOP (on Broad Street, Oxford) would also play a prominent role in selling some of the first copies of The Silmarillion on publication day in September 1977.

More obscurely, KEMP HALL BINDERY (KHB)—who were closely linked to the business of binding books in and around Oxford—were, by the late 1970s, also owned by Blackwell's; although they were still a separate entity in 1960, at the time of this publication. Blackwell's effectively ended their direct involvement in printing in the early 1980s; the KHB group still exists today.

|

| Title page |

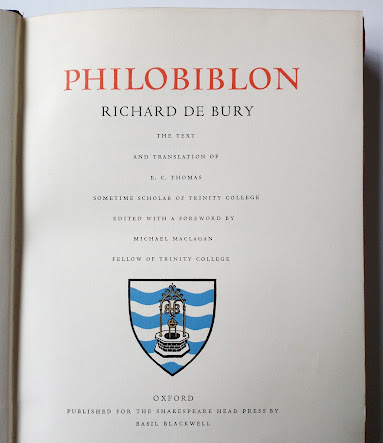

Apparently the Philobiblon was one of Blackwell's favourite books. There is no evidence Tolkien read it; Cilli makes no mention of it in his Tolkien's Library: An Annotated

Checklist (Luna Press, 2019 [2nd Ed. 2023]). This 1960 edition has the 1888 text and translation by Ernest C. Thomas—probably the translation Blackwell would have been familiar with—with his Introduction, Latin text, and English

translation ‘reprinted almost unaltered’; Thomas' associated

biographical and bibliographical apparatus are also included.

Michael Maclagan (the editor)—looking over the shoulder of both the translator (E. C. Thomas) and the author (Richard de Bury)—states that Thomas ‘devoted more time to bibliography than to being a barrister’, and that he was ‘a one-book man, and that book was the Philobiblon’. Maclagan's Postscript gives a useful list of modern editions from Thomas (1888) down to the (then) present (1955), listing some seventeen or so; British, American, and European.

The location and details of manuscripts is also given; Thomas lists nine at Oxford (two in the BODLEIAN LIBRARY), Maclagan adds a few more. It is mentioned more than once how popular the Philobiblon was on the Continent and abroad—especially in Germany—in comparison to the poverty of attention it received at home (in England). Maclagan bemoans that this is still the case in 1960.

The Philobiblon is strangely readable for something written nearly seven-hundred years ago. As

Maclagan points out, many parts are entirely relatable to the book-collector of

1960; much of it is still applicable today. Maclagan suggests that every reader will have their own favourite passages. I suggest, if any chapter should be read in isolation, it should be chapter

seventeen. De Bury rages against readers, denouncing their careless handling of books; youths bedew pages with ‘ugly moisture’ from their noses, have ‘fetid filth’ under nails, and further wet books with their ‘spluttering’ while talking. The condemnation is withering; it's an amusing read.

I won't attempt a chapter-by-chapter summary, I'm sure that can be found elsewhere online. The text is public domain. As an alternative to this, I offer up some notes, that I wrote while briefly re-reading. I hope they illustrate the kind of topics Richard de Bury covers over his twenty chapters. I leave them unedited and without comment.

![[The] Silmarillion; book-collecting minutiae](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/a/AVvXsEi7NXZeS-e6C3roxz2c7UWFEcUEINpMfgDkihMCeoVgjBGA-K9_wE7HmJ0J5LSIJqNm8fDVUqJ5HOvdvgIHgPctu9xPEx_CjPUqrXJEyd5Q-ftA4tlo6NhRx3V9JZl-IBbGvIvBQVjE9GFyKMqd_JrWwkLEqMMbhG2m3Q3FQuyhnjhlhdpebGxovD9adS1H=s456)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment